Wrong! The factors that are the most highly ranked risks to health aren’t the individual health behaviours that appear on most medical lists.

While smoking, drinking or obesity are serious health risks, based on the epidemiological research, not receiving social support and not being socially integrated ranked as the highest.

The rankings were based on analysis of 148 studies, covering nearly 300,000 participants.

Joanna Wilde is a psychologist who is called into workplaces when things have gone wrong. She is also a member of the Health and Safety Executive’s workplace health expert committee.

Joanna gave a presentation to Prospect’s Path to Prevention conference for health and safety reps in early April.

“The epidemic of work-related stress is an epidemic of mental injury in the workplace,” she said.

Like mesothelioma, mental injury takes time to manifest itself. The question should be ‘What happened to you?’ not ‘What’s wrong with you?’ she said.

Joanna believes workplace practices are leading to this dire situation.

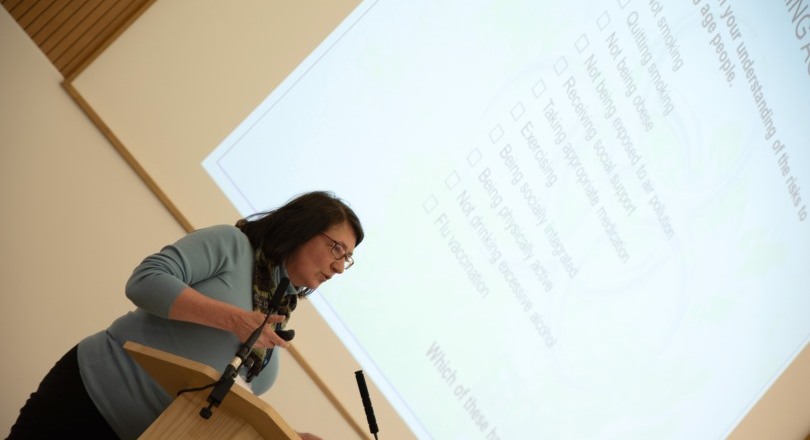

She showed the audience a list and asked them to rank the key risks to health for working age people. The results were surprising – scroll to the bottom of this article to see them.

“Who knew that solidarity was so important to human health?

“It has taken a while for the science to catch up with what we knew. There is not enough recognition of the importance of social networks/solidarity in preventing stress at work,” she pointed out.

Adversity, injustice and health

Joanna talked about the growing attention to the social determinants of health inequality.

Racism and poverty have been recognised as determinants since the 1900s. But precarious work – and the psychological and economic insecurity that comes with it – has recently been identified as an emerging determinant.

She also highlighted the health conditions related to chronic stress: cardio-vascular reactivity, sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight) and inflammation and immune dysfunction – also known as “allostatic load”.

Allostatic load is when chronic stress builds up and has it profound, long-term health impacts.

HSE Management Standards

HSE’s Management Standards established a framework to help employers tackle work-related stress and reduce the incidence and negative impact of mental ill health.

Joanna said the standards have always located the problem in the context of the workplace, not the individual.

They cover six key areas of work:

- demands

- relationships

- support

- control

- change

- role.

HSE’s workplace health expert committee has highlighted evidence that two more categories are also of importance: participation and workplace justice.

What we need to deal with adversity

Joanna outlined the mounting evidence of social factors that mitigate health damage from earlier adversity.

Resilience comes from relationships and resources – deep seated social support needs adequate resources. But she cautioned that too much leadership, engagement, competition and measurement – and too many well-being initiatives – can be counter-productive.

Social identity

Membership of groups improves health – but if a group is stigmatised, it can compromise that benefit, she said.

Equalities are a health at work issue because stigma has an impact on social identification and leads to health being compromised via two routes:

- being excluded from a meaningful group (ostracism)

- being treated as part of a stigmatised group (discrimination).

Pulling lots of different people together is a complex, shared task which needs resources.

Case studies

Joanna described three case studies that she had been involved with. Much of her work is confidential, so she could only share snippets. However, they do illustrate workplace practices that leads to key social deficiencies.

Case study one: A shift-based industrial setting

Joanna was called in to an organisation where:

- the number of people experiencing stress was increasing

- length of absences were rising and

- repeat absences were increasing.

The root of the problem was a change in the rostering set up. Groups of people had been broken up by the new rosters. People were randomly allocated to roster by a machine rather than a person.

People felt really lonely, managers had lost any sense of what was going on and a well-connected environment had been broken.

When people were coming back to work after an absence, there was no one to look after them. They were given a checklist rather than a person to talk to. The changes had taken their toll on the union rep too.

Joanna organised job crafting sessions aimed at finding out what changes were needed to improve the set up.

Participants were asked what resources they needed and what demands on them needed attention.

The answers weren’t complicated. People wanted someone to talk to rather than having to fill out lots of stupid checklists.

They also wanted human control over rostering and for the organisation to look at how the work environment was monitored.

Research explicitly classifies the types social deficiencies in the workplace that have an impact on social support and social integration:

- a sense of isolation or ostracism

- a lack of connection to the people who can help you do your job.

Joanna advised the organisation to do a risk assessment looking at social support before making changes and to look at social integration.

“Social integration and social support at work can be seen as a form of personal protective equipment. It’s not just good for productivity, it is critical to health,” she added.

Case study two: Justice at work

Joanna was called in to a construction site in a remote area and given a walkabout role.

The 150 bricklayers were grumpy and incident rates were going up, despite audits and external advice.

Joanna soon became aware that the bricklayers has a sense of injustice and she suggested sessions for everybody.

Her first question was why the company was bringing in outsiders to look at the problem? Why didn’t it ask the workers?

She organised 90-minute voice sessions, with 10-15 people per session. She asked participants “What’s it like to work here?”

The resounding answer was that it was unfair. The bricklayers were all on different contracts and not paid the same. The sessions explored how they came to be on the contracts they were on.

The incident rate dropped as a result of the sessions. Although they didn’t resolve the pay issues, they did allow people to speak up.

The health risk was mitigated by speaking, sharing and discussing the issues.

“If we only focus on procedures, we don’t treat people as people. It’s not what, but how, people are treated in any procedure,” said Joanna.

Justice dynamics

Distributive justice – perceptions of fairness about job outcomes. For example, employees with the same or similar work experience and time on the job are promoted or transferred equally.

Procedural justice – involves fair procedures. It allows employees to have a say in the decision process, it treats them fairly and allows them to have more input in the appraisal process.

Interactional justice – the degree to which the people affected by decisions are treated with dignity and respect.

Informational justice – adequacy of the explanations given in terms of their timeliness, specificity and truthfulness.

Case study three

Joanna helped a young black woman who had completed a graduate management programme. Joanna described the way she had been managed as “horrifying”.

Joanna urged her to take time away from work. But the young woman was nervous. Her manager had told her that taking time off would send a message that she couldn’t cope and her career would be over.

He had told her that she had to be better than everybody else.

Colleagues who had witnessed how the young woman was treated were also distressed.

Staff surveys had shown that this part of the business had a problem.

Joanna interviewed the young woman’s manager who said that his reputation could be damaged if the young woman took time off because of stress and that he had taken a risk by hiring a black person.

“The manager’s behavior was a risk to the young woman’s health and to the organisation’s reputation.

“This is common. There are a lot of very, very bad managers out there,” said Joanna.

She pointed out that the consequences for managers like this would be very different if they were that cavalier with financial resources.

The young woman is now thriving and says that counselling was one of the best things she had ever done.

“We know that relationships matter, resources matter and that appropriate sanctions are critical,” concluded Joanna.

Risks to mortality for working age people – rankings based on systematic review (Holt-Lunstad et al 2010)

- Receiving social support

- Being socially integrated

- Not smoking

- Quitting smoking

- Not drinking excessive alcohol

- Flu vaccination

- Exercising

- Being physically active

- Not being obese

- Taking appropriate medication

- Not being exposed to air pollution